Dr. Dorothea Depner

When we speak of Castletown House we tend to seize on its architectural significance as Ireland’s first and largest neo-Palladian country house and focus on the house’s heyday in the eighteenth century to the exclusion of later periods. At the time, it was proclaimed ‘the only house in Ireland to which the term palace may be applied’ and was synonymous with fine style and lavish entertaining that rivalled the viceregal court in Dublin. Built between 1722 and 1729 for William Conolly (1662-1729), Speaker of the Irish House of Commons, Castletown was intended as a political and social centre commensurate with his influence and immense wealth. Although none of his heirs lived up to his stature, the house flourished when his great-nephew Thomas Conolly (1738-1803) settled there in 1759 with his young wife, Lady Louisa (1743-1821). The daughter of Charles Lennox, 2nd Duke of Richmond, Louisa brought with her the style and refinement she had been accustomed to at her childhood homes in Carton, Goodwood and Richmond House, and set about modernising her new home to suit her tastes. Her influence is still omnipresent today, be it in the interior decoration she commissioned – the beautiful cantilevered staircase, the exquisite plaster decorations, the stunning Long Gallery or her own carefully curated Print Room, to name but a few – in the parkland she designed stretching towards the river Liffey or in the state-of-the art home farm built to her specifications. After her death, Castletown passed to the son of one of her husband’s nieces, and comparatively little is known about his interventions or life in Castletown for subsequent generations of Conollys until the sale of the house at auction in 1965. Yet even though the family fortunes turned in the nineteenth century and investment into the house was scaled back, the rooms in Castletown today still bear witness to this later layer of history and interior design. None more so, perhaps, than the Red Drawing Room, or, as it was known in the Victorian period, the Crimson Drawing Room, named for its most distinctive feature: the crimson and white silk damask that covered the four walls, most of the seating furniture and that framed the three windows.

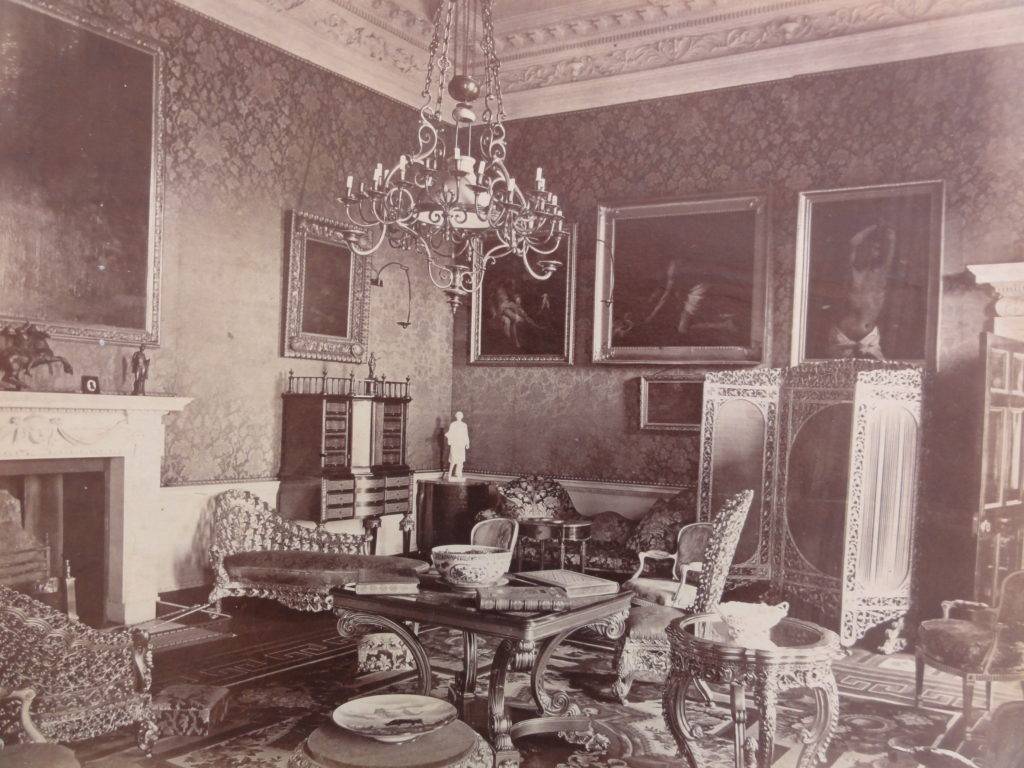

Photograph of the Crimson Drawing Room c. 1880 by Henry Shaw (courtesy of Chris Shaw)

The above photograph taken by Henry Shaw – brother of Eliza Shaw, who had married Thomas Conolly II in 1868 – shows the Crimson Drawing Room not long after its completion in all its splendour and gives a glimpse of the heady mixture of periods and tastes it combined: in the corner is one of a pair of Lady Louisa’s French cabinets by Lacroix (bought for her in Paris by her sister Lady Caroline Fox in 1763), an array of exotic Bombay gilt furniture with its lace-like carvings is arranged around the centre of the room, and a collection of predominantly large religious paintings by famous Old Masters such as Vasari, Murillo or Mazzolini hangs against the backdrop of the patterned silk. This opulent scheme was devised by Thomas Conolly (1823-1876), whose habits were every bit as sociable and spendthrift as those of his ancestor of the same name. He sought adventure abroad and became acquainted with such illustrious figures as Napoleon III in Paris as well as General Lee in Virginia. During the American Civil War, he attempted to restore his family’s fortune through blockade running (he failed) and kept a diary on the fall of the Confederacy. After Thomas returned from his travels, he married Sarah Eliza Shaw, the daughter of Joseph Shaw, owner of the Celbridge Paper Mills which were one of the largest industrial complexes in Ireland at the time. Together they travelled to Italy in 1870/71, and although no account books of the period survive, it is most likely that Thomas embarked on the refurbishment of the Crimson Drawing Room shortly afterwards with funds supplied by his wife’s dowry of £10,000 (worth over £1,000,000 today). It may even be that the silk itself was ordered from Italy, as recent research has shown that the unusual artichoke and leaf pattern in Castletown can be found in the Sala delle Udienze in the Royal Palace in Genoa and, in green silk, in the Salone Verde in Palazzo Pitti, Florence. In the absence of account records for that period the exact provenance remains a mystery, but what can be said with certainty is that the damask was of the highest quality, its lustre and two tonal design the product of unsurpassable hand weaving on Jacquard looms.

The Red Drawing Room prior to conservation (Photo by Con Brogan, National Monuments Photographic Section)

However, over the course of more than a century both the Crimson Drawing Room and the fabric changed appearance. Most of the paintings and furniture were irretrievably lost at auction sales, the curtains and light fittings disappeared, and the vibrant fabric itself suffered from exposure to light, heat, and careless handling. By the time Castletown came into State ownership in 1994, the house’s interior and exterior needed extensive repairs, but once those were completed in 1999, ‘the conservation of the embrittled mid-nineteenth-century silk damask wall hanging in the Red Drawing Room’ was identified as a next priority in Building for Government: The Architecture of State Buildings. Several reports were commissioned from different textile conservators, but it was only when the silk was understood within the context of the multiple historic layers that define the Red Drawing Room today – and the Red Drawing Room’s place within the ensemble of rooms that constitute the north enfilade in the house – that the project could be embarked on with confidence. Launched in 2015, this conservation project currently includes three partners – the OPW, the Castletown Foundation and the Apollo Foundation – and involves three different aspects of conservation and restoration, all of which aim to restore the historic character of the room: the conservation of the original nineteenth-century silk wall hangings, the replication of the original silk for curtains and drapes similar to the ones that were once in the room, and the curation of a Grand Tour picture hang and furniture arrangement in the spirit of historic records as far as possible.

Over three years, two textile specialists, May Berkouwer and Ksynia Marko, carefully conserved the silk panels in situ, one wall after the other. They developed methods to tackle even the most difficult areas, and the result is a harmonious, intact appearance of the treated walls where faded areas have been revived, areas of loss have been successfully infilled with silk dyed in a matching colour and tears have been closed in such a way that they are no longer visible. If you click on the image below, you can watch a short video we put together to explain the scale of the project and the intricate steps involved in securing the silk, and you can see for yourself how it looked before and after conservation.

May Berkouwer shown infilling a split seam join on the West Wall – click on the image to watch a short video documenting the conservation (photo by Trinity Digital Studios, OPW)

With the walls fully conserved, the cleaned and touched-up gilded fillets were reinstated at the top and bottom of the silk panels, creating a wonderful frame for the precious fabric. A picture rail in a matching red was then installed in preparation for an exciting new picture hang of Old Masters on loan from the Schorr Collection.

In parallel with these conservation works, Humphries Weaving in the United Kingdom was commissioned to faithfully copy the intricate design and weave of the wall hangings and to develop red and white silk threads that match the colour of the vibrancy of the original silk. Although their looms are not the same as those that were used in the nineteenth century, the silk reproduction they produced is remarkably like the original. The new fabric has been used for three pairs of curtains to dress the windows and to reupholster some of Lady Louisa’s Chinese Chippendale chairs, which are still in Castletown and which we know were covered in the same fabric as the walls when the Crimson Drawing Room was refurbished in the 1870s.

A glimpse of the Red Drawing Room with its new curtains, re-upholstered chairs, conserved silk wall coverings and exciting new picture hang (photo by Paul Tierney)

Whether you recently visited Castletown and saw the conservation in progress or whether you’ve never been, this is the perfect opportunity to visit and admire the conserved Red Drawing Room and to discover, or rediscover, a whole new facet to this Italian palace on the banks of the Liffey!