Speaker William Conolly died at his house in Capel Street on 30th October 1729 having collapsed in the House of Commons ten days earlier. His death was lingering, with Thomas Pearson talking of blisters on arms and thighs, continuing fluxes and purges and a fever.

23 Oct. 1729. Thomas Pearson, Dublin, to Mrs Bonnell.

‘I much fear he cannot hold out very long now. He has his senses, except when he wakes out of his dozing fits, and seems desirous of dying in a very composed manner. … Friday morning. He has had several clysters given him but he does not keep them, and his purging is as great as ever, so that I cannot see what can be done for his service. He is very weak, and has not rested well.’

William’s funeral was held on the 4th November. This was a significant date in the protestant calendar as it was William III’s (William of Orange) birthday. This fact was probably not lost on his wife Katherine.

Heraldic Funeral

Historian Patrick Walsh tells us that ‘widows played a key role in maintaining their husband’s posthumous reputation, political and personal’. Katherine organised an elaborate heraldic funeral described as ‘the limit of what was acceptable and what was seen as vulgar excesses of a self-made man and his devoted socially ambitious widow’. It was a heraldic funeral stage managed by the Ulster King of Arms. Normally this type of funeral was suitable for royalty and senior members of the aristocracy. It did not bother Katherine or many of the observers, one of whom called it ‘the finest funeral that has been seen in this kingdom in many years’. Certainly, it was more impressive than that of Archbishop King who had died the same year as William.

Katherine decorated their Capel street house in black fabric, including the reception rooms and the staircase. Sixty-seven poor men dressed in black walked in front of the coffin, one for each year of William’s life. The Members of Parliament processed in pairs with the Lord Lieutenant leading them. There were 700 mourners who walked with the coffin from Capel Street to the end of Arran Quay on foot, many of whom travelled on to Celbridge. Francis Burton, Katherine’s nephew, explained that everyone had a linen scarf of three yards at the rate of 6s. a yard saying ‘Tis a custom introduced for the good of the kingdom. And which if it continues will create a great consumption of your own manufacture’. He is suggesting it is better to support the Irish linen industry rather than French silk. Katherine arranged for the distribution of expensive mourning rings to friends and family. William left a large amount of money in his will for the funeral and an extra £1000 for mourning clothes and rings. The following is an excerpt from the Dublin Weekly Journal on the 8th November 1729.

Last Thursday the Hon. William Conolly Esq. was carried along the keys from his late House in Capel Street to be interr’d at Cell-Bridge, in the following manner William Conolly esq. nephew and chief mourner. The High Constable with a Shrfe, and Six of the Lord Mayor’s Constables with Hat Bands and Gloves to clear the way. Poor men in Black Cloath Serge Gowns, in number 67 according to his age, each carrying in his hand a Penuoncil with the letters of his age. Three pursuivant messengers in their liverys. Surgeons and Apothecary Physicians. Lord Mayor, Recorder, Aldermen and Sheriffs in their formalities Edward Dearing Esquire Clerk of the Council. The Helmet and Crest caried by Athlone Pursuivant in his Coat. Messengers and Door Keepers to the House of Commons bare headed. Sergeant at Arms and his Deputy to assist him with Servants. The Coat of the Defunct’s Armes carried by Ulster King of Armes in His Majesty’s Coat. His Excellency the Lord Lieutenant’s Coach, with men ushers and bedchamber. His Privy Councillors, supporters of the pall. Members of the House of Commons, two and two. Nobility and Gentry, two and two, and all with linen scarves of Irish manufacture.

The Conolly funerary monument

The funerary monument finally cost £2000, took four years and necessitated two extensions to the church in Tea Lane, Celbridge to accommodate it.

The statues were by Thomas Carter of London and made the papers the day they arrived in Ireland in 1736 from Hyde Park in London. They are exquisite in their attention to detail and bear a striking resemblance to the Charles Gervas painting of William and Katherine in Castletown. Carter and Gervas were acquainted and Gervas had loaned Carter money to extend his London studio. It could be reasonably assumed then that Gervas was responsible for Carter gaining the commission.

British sculptors of the seventeenth century had used a variety of devices to express which of two-life size figures the living donor in the monument was. From the later part of the century, sculptors such as John Nost developed fluid poses showing a mourning character gesturing down to the recumbent object of their sorrows. One of the most popular ways of doing this was to build a two tier base for reclining figures showing the living donor above looking at the object of their affection or out at the viewer. A wonderful composition of this type was in 1711 by John Nost for James Douglas, the second Duke of Queensbury and his wife Mary at Durisdeer (below left). The person who has died is often displayed more splendidly than the surviving partner is. The Conolly monument is very much in this style (below right).

Only the statues were mentioned in the papers, so we assume that the framework was already in place, having been made in Ireland. It is believed to be the work of William Kidwell.

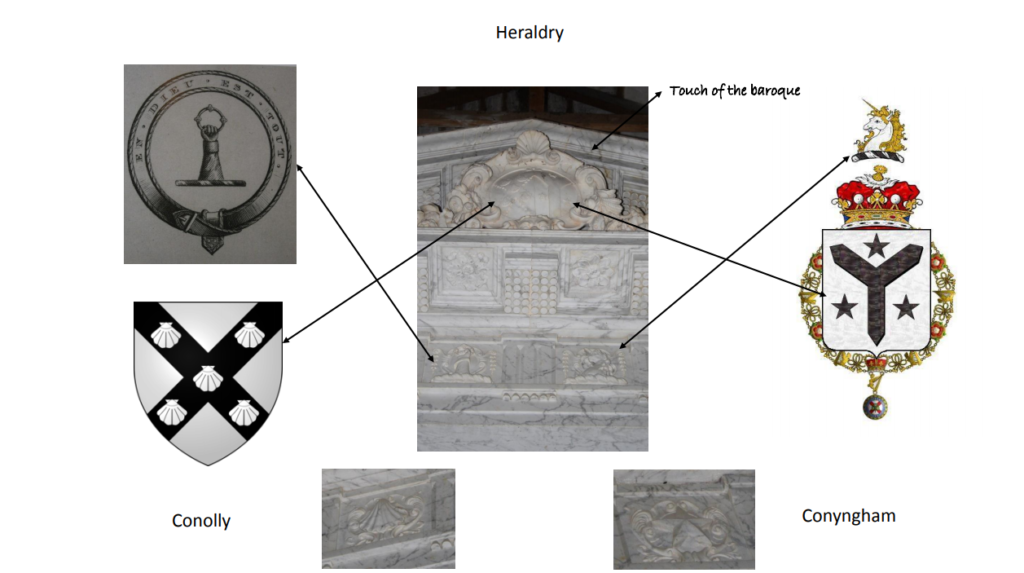

The framework of the monument is heraldic in design. The triangular pediment has the ‘New’ crest William was considering (cross with five scallops) and the Conolly crest in the marble entablature. The Conyngham crest is equally well represented, the Y with three stars and a unicorn. The two families are represented by scallops and stars throughout. These are described in the Dublin Historical Journal as

- ‘Argent on a saltier engrailed sable, five escallops of the field’ -for Conolly.

- ‘Argent, a shake-fork, between three mullets. Sable’ -for Conyngham

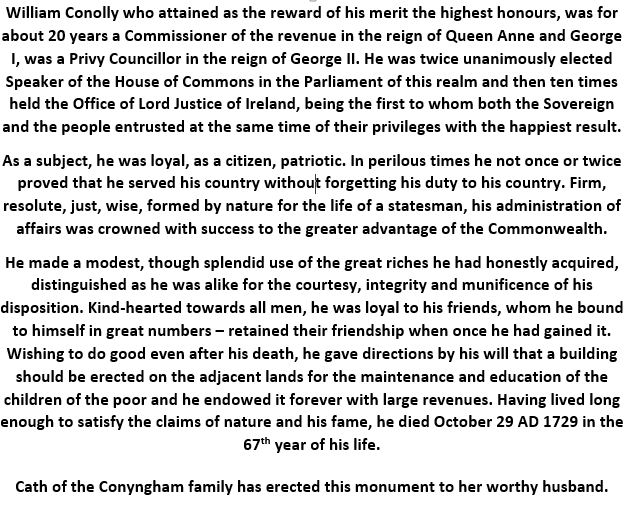

Although Katherine and her family name are represented in the design, the Latin inscription only talks about William. It describes his many public offices and achievements, his loyal friendships and his charitable endeavours. The monument was intended as a site of public commemoration and veneration. A place to remember the great man. The following is an English translation of the Latin inscription:

Katherine’s choice of the phrase ‘honestly acquired’ must have amused many of the contemporary viewers.

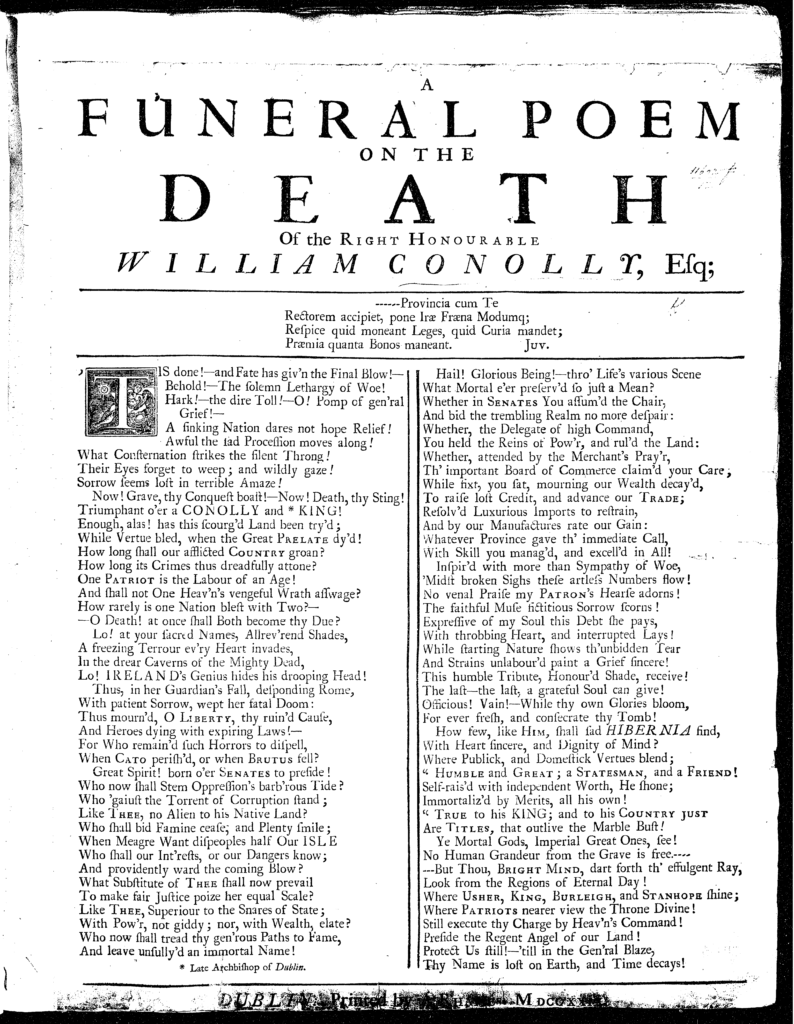

‘A funeral Poem on the Death of William Conolly’ (see end of article)

The fashion for composing elegies exploded in Dublin in the 1720’s. They were normally written for Kings, Queens, lords and ladies. In the 17th century, the death of these high-ranking individuals warranted a very lengthy poem by an established author published in pamphlet form. From the early 18th century, they grew to include civic and political figures in Ireland like Squire Roberts (The overseer of the Custom House who died in 1727) and William Conolly. William’s poetic elegy was written by James Sterling and is very positive to William and indeed to Archbishop King who died the same year. The Conolly’s supported Sterling earlier in his career so it was highly unlikely he would have been critical!

‘Now! Grave, thy Conquest boast! – Now! Death, thy Sting!

Triumphant o’er a CONOLLY and *KING!’

Personal grief

It is too easy to forget that in the midst of the pomp and ceremony a devoted spouse lost her husband, and lost him early.

26th August 1731. Katherine Conolly to her sister Mrs Jane Bonnell describing the mourning ring she wishes to have made to remember William.

‘I think a good transparent diamond over it (lock of Williams hair) –two diamonds, I mean brilliants in each side with a heart on each side of a death’s head, with this motto, we part no more’

She subsequently sent the design and some of William’s hair to Jane on the 30th September 1731. She also asked her to be careful and check that the real hair was used as she had heard of a case where it had been replaced by thread of the same colour.

9 Nov. 1729. Francis Burton, Dublin, to Mrs Bonnell, London describing Katherine in the days after William’s funeral.

‘My poor aunt is going the ready way to destroy herself. She neither eats, drinks nor sleeps, is really fallen away to nothing, nor will she be persuaded to take any one thing that is proper to support her spirits and comfort her.’

9 Dec. 1729. Francis Burton to Mrs Bonnell describing Katherine’s living space. I could be argued he is not entirely happy with her choices.

‘She begins to see her particular friends, has her own apartment [in Speaker Conolly’s house in Capel Street, Dublin] hung in grey and the great stair case and the great apartment above stairs in black where I suppose she must see company in form, which will be a most disagreeable entertainment. The floor of the great bedchamber is covered with black which I suppose will be a matter of great observation to the town being usual only to persons of the first quality.’

William did leave Katherine well provided for as Thomas Pearson tells her sister on 30th October 1729.

‘I am now to acquaint you of the death of Mr Conolly. … He died about one this morning. … He has left my sister the house in town, all his estate in Kildare, Meath, Westmeath and Roscommon, for life, and the estate in Wales for ever, with his plate, and furniture in both houses during life, and £1,000 legacy.’

Katherine would live on into her 90th year, spending 23 years as a widow. She built lasting monuments in William’s honour and ensured that a man whose house was not finished at the time of his death would be remembered there 300 years later.

Building a Legacy

William wrote his final will in 1729 just 11 days before he died. In the will, he set about building a Conolly legacy and ensuring his own legacy. His decision to be buried at Castletown was significant, signifying his attachment to Castletown and not his home town of Ballyshannon or even Dublin where his political career had thrived.

He also left a large sum of money to erect a school for 40 orphans or other poor children. He added that £250 a year for the running of the school was to come from the money issuing from the manor town and lands in Rathfarnham and another £250 from his estate via his executors. The school deviated from the norm at the time as it was to be residential and not a day school and no discrimination in respect of religion was to be made. The Incorporated Society for Promoting English Protestant Working schools in Ireland had opened the first of its schools in Castledermot three years previously and always wanted to gain control of the Conolly’s school. They did not succeed until 1809 when Lady Louisa transferred control. It continued for another 160 years, contrary to William’s wishes, educating only Protestant girls.

The Conolly’s had no children and creating a funerary monument and death house ensured a closer relationship in death than in life with their heirs. Tom Conolly went a step further in his will by ensuring an heir of his would take the name Conolly and make Castletown their primary residence. Clodagh Tait suggests that ‘elaborate monuments and carefully choreographed heraldic funerals were used by those whose social position was recently acquired to demonstrate their new place in a mobile social order and to shake off all vestiges of their origins’.

The Conolly’s of Castletown had arrived.

By Celine Hanratty, Castletown Guiding team.